A Selex EX Falco unmanned aerial vehicle, or drone, of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) crashed today. The aircraft crashed at the airport in Goma in Eastern DRC, where the aircraft are based. There does not appear to be any reporting yet on what might have caused the crash. Initial reporting by the wire services, variously citing DRC or UN officials, seems suggest there is some uncertainty about whether the aircraft was leaving for or returning from a mission.

Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The city of Goma in the highlighted zone has historically been a major point of contention in the region.

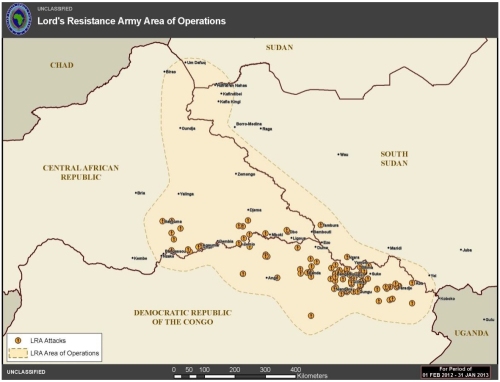

MONUSCO only received the drones at the end of 2013 and they were expected to help monitor the activities of the numerous armed groups active in DRC. If there have been no additions to the proposed force, then this reduced the MONUSCO fleet to four unmanned aircraft. Later reports indicated that the drone’s surveillance equipment was undamaged and repairs would allow the aircraft to return to operations.

Concerns about the basic safety of drones have been a matter for debate domestically in both the US and Europe, and were also said to have been the primary motivator for moving US drone operations in Djibouti from Camp Lemonnier to a remote desert airstrip, Chabelley Airfield, last September. The issue of basic safety in these operations will no doubt become a matter of debate in this instance as well.

A team of technicians prepare a Falco unmanned aerial vehicle for the inaugural flight in Goma, North Kivu province, during an official ceremony organized in the presence of Under Secretary General for Peacekeeping Operations, Herve Ladsous, on 3 December 2013.

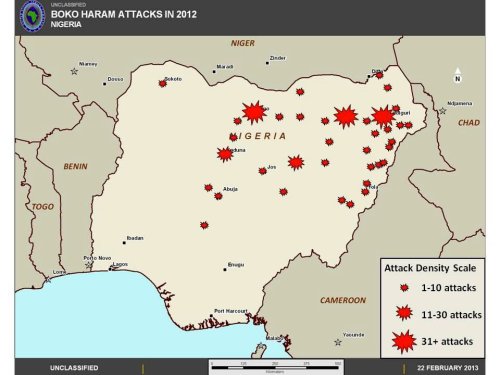

The crash also comes as the UN reports that elements of M23 may be active again and possibly recruiting new fighters. Representatives for M23 have denied this, but that very fact highlights what has been said here and by other observers about the ongoing uncertain. M23’s final status remains up for debate, and accusations about support from Rwanda and Uganda remain unresolved. This potential connection should not be dismissed out of hand, especially in light of accusations that Rwandan authorities orchestrated the murder of a Rwandan dissident in South Africa earlier this month. Even if M23 is gone for good, there remains a significant number of rebel groups that threaten security in eastern DRC, such as the FDLR, which MONUSCO said it would focus on following the military defeat of M23 last year.